Fan power drives Japan’s Racing Club phenomenon

Japan’s racing clubs are synonymous with some of the JRA’s most famous horses, and club silks will be prominent again at the Dubai World Cup fixture, driving fan engagement at home and abroad.

BRINGING ASIAN RACING TO THE WORLD

Japan’s racing clubs are synonymous with some of the JRA’s most famous horses, and club silks will be prominent again at the Dubai World Cup fixture, driving fan engagement at home and abroad.

When Japanese-trained horses won five of the eight races at the Dubai World Cup fixture in 2022 it was a high-profile continuation of Japan’s impressive run of international success across the preceding year. But what was also noticeable was that four of those victors raced in the colours of multi-share racing clubs.

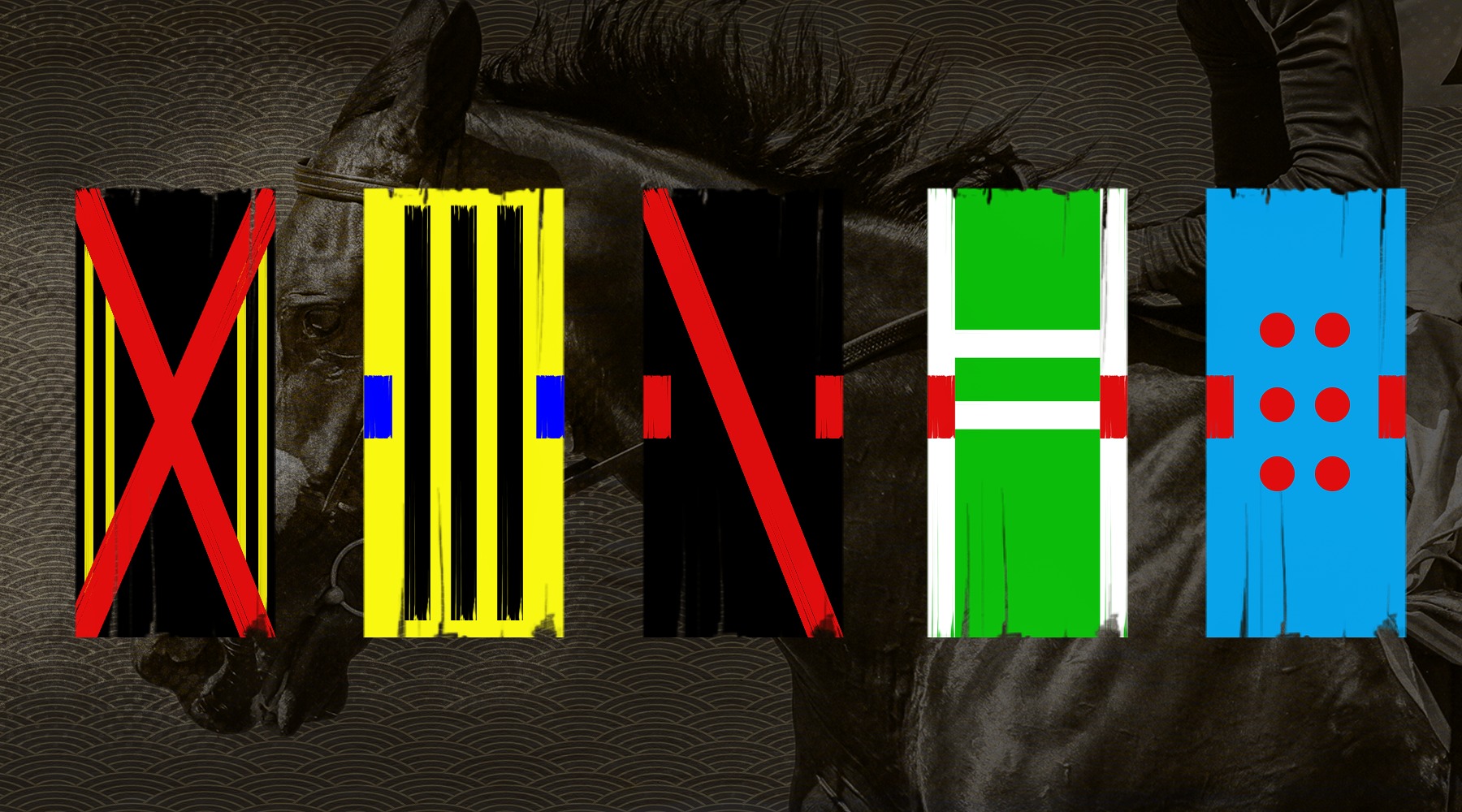

Panthalassa and Bathrat Leon triumphed for Hiroo Race Co Ltd, Shahryar was successful for the prominent black, red and yellow silks of Sunday Racing, and Stay Foolish was on the mark for the granddaddy of all such clubs, Shadai Race Horse Co. Ltd.

Racing clubs accounted for no more than 23 of the JRA (Japan Racing Association)’s 2,672 registered owners at the start of 2022, yet, despite representing less than one percent of that whole, those clubs account for about 17 per cent of just under 9,000 horses in the racing system. And several of those club syndicates achieve success at the elite end of the sport on a scale not seen by similar entities in other major racing jurisdictions.

On the eve of the 2023 Dubai World Cup meeting, horses owned by racing clubs account for about half of Japan’s 27-strong raiding party.

The list of big-name horses – champions in several cases – that have been ‘owned’ (we’ll come back to that shortly) by fans via a variety of racing clubs is long and features such stars as Almond Eye, Orfevre, Cesario, Lord Kanaloa, Gentildonna, Lys Gracieux, Gran Alegria, Chrono Genesis, Epiphaneia, Buena Vista, Daring Tact, Loves Only You, Efforia and Equinox.

These clubs, which break down individual horse ‘ownership’ into shares and offer their members opportunities to participate, are nothing new and they are certainly not peculiar to Japan. Similar multi-share concerns like Team Valor, the blue-collar Elite Racing Club in Britain or the Classic-winning Highclere, with its middle-class reach spanning Europe and Australia, are long-established; in Australia, syndicates of all types and sizes have enjoyed a boom in recent years.

Yet where else but in Japan has such an ownership model dominated the Group 1 ranks and topped the leading owner charts every season going back 40 years?

The reasons for the Japanese clubs’ lofty achievements can be distilled to two principal elements: a hearty appetite for closer engagement among the sport’s fervent followers, and the Yoshida family’s influential Shadai Group thoroughbred enterprises.

In fact, Shadai’s prominence in the racing club sphere speaks to the most striking difference between the Japanese model and most club models elsewhere in the world: close partnerships between the clubs and stud farms. Think of a dream scenario in which Coolmore or Juddmonte enable most of their best stock to race for affiliated public syndicates and you have something like the Shadai Group reality.

Since the first of the Yoshidas’ five prominent clubs, Shadai Race Horse Co. Ltd., was established in 1980 it has been the JRA champion owner 25 times, including consecutive seasons from 1983 to 2004. The only other champion owners since 1983 have been the Yoshida family-related clubs Sunday Racing and Carrot Farm, with Sunday carrying off the title 13 times since 2005 – including each of the last six years – and Carrot topping the table in 2014 and 2016.

“These clubs have a lot of runners and by having success at Group 1 level, their colours are seen all over the world, and that does encourage people to get involved. That’s why, I’m sure, the Yoshida family has all of these clubs,” said Murray Johnson, the JRA’s English language race caller.

“The more success the club syndicates have, with the fans involved, word of mouth and good results encourage people to maintain their interest or to actually sign up in the first place.”

Silver Sonic wins at Riyadh for Shadai Race Horse Co. Ltd. (Photo by Lo Chun Kit)

People power

Those passionate fans are a large bloc at the heart of Japanese racing culture. The racing club phenomenon is tied to a cognisance among the industry’s decision makers that within a government administered pari-mutuel system that feeds betting income back into the sport, expanding the interest of those everyday race fans is vital to sustaining the whole caboodle: these are the people that helped push the JRA’s annual horse racing turnover to ¥3,269,118,996,100 (approx. US$24.7 billion at the March 2023 exchange rate) in 2022.

Horse racing in Japan has evolved in such a way that it takes the foundation blocks of sport and gambling and adds layers of fan-involved pop culture; elements such as anime, gaming and celebrity. The opportunity for a common fan to own an affordable share in a racehorse via a club syndicate is an extension of the connectivity that sees those same individuals hook into the Uma Musume ‘Pretty Derby’ multimedia franchise or spend their income on branded merchandise like jackets, flags and soft toy ‘plushie’ versions of their favourite hero horses, available at the JRA’s Turfy shops from Kokura to Sapporo.

“Buying a horse is tough, it’s an expensive hobby and the club syndicates make it easier for normal people to get involved as owners,” said jockey Mirco Demuro, who rode Uberleben to Oaks success in 2021 for Thoroughbred Club Ruffian.

“Imagine it: normal people could buy Almond Eye. That makes it a joy for so many more people who would not ever have been able to own a champion like that.”

Uberleben’s ownership under the Thoroughbred Club Ruffian banner was broken down into 100 relatively affordable shares at 150,000 yen (approx. US$1,220) each. Similarly, two of Japan’s five Dubai World Cup meeting winners in 2022, Panthalassa and Bathrat Leon, brought jubilation for their everyday shareholders within the Hiroo Race Co. Ltd. The Dubai Turf dead-heater Panthalassa’s ownership is made up of 2,000 shares, each valued at ¥25,000 (approx. US$203), while the shareholders of Bathrat Leon, the Godolphin Mile winner, paid just ¥17,500 (approx. US$142) for each of 2,000 shares.

Panthalassa has carried the colours of Hiroo Race Co Ltd to some spectacular victories. (Photo by Francois Nel/Getty Images)

And then there is the DMM Dream Club Co. Ltd., the micro-share enterprise that raced Loves Only You, Japan’s star globetrotter of 2021 and a Classic winner thanks to her success in the 2019 Japanese Oaks. During her pinnacle campaign as a five-year-old, she annexed the G1 QEII Cup and G1 Hong Kong Cup at Sha Tin and became the first Japanese-trained winner of a Breeders’ Cup race for the several thousand ‘owners’ who invested in the syndicate.

The club is part of the DMM.com experience, which has around 35 million registered users accessing adult content, mainstream video streaming, online shopping, games, e-books and more. That such a large concern has tapped into the racing club market speaks to the scope of the sport’s fanbase in Japan. DMM Dream Club, with its digital elements being part of the investor experience, has provided an affordable Group 1-winning ownership route very much outside of horse racing’s old stereotype model of ‘rich establishment man owns a horse’.

“If fans take one share in a horse it means that those fans feel what ownership is like, it strengthens their connection to the horses and to racing,” said Masashi Yonemoto, the CEO of Silk Racing Co. Ltd., which raced the great mare Almond Eye and has the current Horse of the Year Equinox.

“In Japanese horse racing culture, betting is a strong element and by owning a share in a horse the fans also understand how difficult it is to get a win while at the same time the horses give us (the racing club and the shareholders) our own story, our own experience.”

Yonemoto leads Silk Racing with his wife Akiko Yonemoto, whose father is Katsumi Yoshida, the head of Northern Farm to which the Silk Racing club is affiliated.

Yoshida influence

The almost omnipresent Yoshida family has long understood the importance of fostering the tighter attachment that develops when regular fans become owners. The family’s Shadai Group of companies, with its three fraternal strands, leads the way in most aspects of Japan’s thoroughbred industry; whatever might have been the initial financial risk associated with breaking from the conventional breeding and ownership models to pursue a racing club-focussed strategy, it has paid off handsomely, not just for the group but for Japanese racing as a whole.

Each strand of the family’s thoroughbred empire is under the watch of one of three sons of the late Zenya Yoshida who established Shadai in 1955. Yoshida went on to become something like Japan’s own incarnation of E.P Taylor, the Aga Khan and John Magnier all rolled into one. He created a mighty racing dynasty thanks to his and his sons’ astute sourcing of quality bloodstock from Europe and the United States, notably the exceptional sires Northern Taste and Sunday Silence.

The eldest of Zenya’s boys, Teruya Yoshida, heads up Shadai Farm, under which the Shadai Race Horse Co. Ltd racing club operates; Katsumi Yoshida’s Northern Farm is affiliated with Japan’s three most successful clubs of recent times, Sunday Racing, Carrot Farm and Silk Racing; and Haruya Yoshida is the head of Oiwake Farm, which runs the G1 Racing Club.

Sunday Racing was set-up in 1986, six years after Shadai Race Horse Co. Ltd.: it was initially known as Japan Diners Thoroughbred Club in collaboration with the Diners Club credit card company, before changing to its current title in 2000. G1 Racing Club was formed as recently as 2010. Silk Racing and Carrot Farm initially had nothing to do with the Yoshida family: Silk came into being in 1985 and developed an affiliation with Northern Farm around 2010, while Carrot Farm was established in 1986 and firmed its ties to Northern close to the turn-of-the-century.

The Yoshida influence is omnipresent among Japan's racing clubs. (Illustration by Sterling Graphic Design)

Shadai Race Horse Co., Sunday Racing and G1 Racing operate towards the elite end of the racing club sphere, offering 40 shares per horse. At the outset of 2021, for example, Shadai Race Horse Co. had 184 horses with shares ranging in price from ¥250,000 (approx. US$2,017) to ¥2.5 million (approx. US$20,175), depending on the horse; Sunday Racing had 192 with shares from ¥300,000 (approx. US$2,421) to ¥3 million (approx. US$24,210); and G1 Racing had 109 horses divided into 40 shares per horse priced from ¥300,000 (approx. US$2,421) to ¥1.5 million (approx. US$12,105).

Carrot Farm had 183 horses, each divided into 400 shares priced between ¥35,000 (approx. US$282) and ¥200,000 (approx. US$1,614), while Silk Racing, with 192 horses split into 500 shares, gave its investors the option of owning a champion like Equinox or the next Almond Eye for as little as ¥25,000 up to a maximum single share price of ¥200,000.

That means the five clubs between them, in that year, made available to public investors a total of 188,600 shares in the ownership of 806 race horses.

Northern Farm’s breeding operation has excelled in recent times, being Japan’s leading breeder for the past 12 years, and that has fed the success of its affiliated racing clubs. Sunday Racing has been the JRA’s leading owner for ten of those years, with its Carrot Farm club having wrested the title in the other two seasons.

Northern Farm effectively decides which horses go to which of the three clubs and sells them for a fee representative of their value. The club investors enjoy ownership of their horse only until it retires from racing (all mares must retire in the March of their six-year-old season, whereas there is no such limit on the careers of entires and geldings) at which point a reverse transaction occurs and they revert to Northern Farm ownership. Whether or not they are retained wholly by Northern or are then syndicated as stallions or broodmares is decided horse by horse.

Each club, whether Shadai affiliated or not, will have different approaches and outcomes depending upon their individual club policies.

How it works

The racing club mechanism involves the setting up of two companies, an Aibakai – effectively a fund, a financial instrument that sources horses and handles shareholder investments – and the club itself, the registered owner with its own racing colours and to which the JRA or NAR pays prize money. In the case of Shadai, the registered racing ownership club is called Shadai Race Horse Co. Ltd, while the Aibakai corporation is listed as Shadai Thoroughbred Club Co. Ltd

Clubs make available a raft of information to potential investors, issuing catalogues and video footage, the same as if an individual was looking to buy a horse from any of the world’s major sale houses.

The catalogues outline each horse’s pedigree, how many shares are available, the cost of each share, which trainer they will join and at which training centre. Shadai Race Horse Co. Ltd.’s 2022 dual Classic heroine Stars On Earth was catalogued at a price of ¥700,000 (US$5,300) per 40th share, while a one 40th share in the same club’s 2022 Dubai Gold Cup victor Stay Foolish was priced at ¥1,250,000 (US$9,500).

Shadai's Oaks winner Stars On Earth. (Photo by JRA)

Costs vary from club to club but as well as the share fee, there is usually an initial enrolment cost, plus monthly membership payments and ‘maintenance’ costs (stabling, vet, entry fees), as well as an annual insurance fee. According to the Silk Racing club website, the monthly cost for a member after investing ¥30,000 (approx. US$232) in a five-hundredth share would be about ¥5,000 (approx. US$39).

Some clubs, such as those affiliated to the Shadai group, will hold open days for their members to view the catalogued horses on site at the farm, prior to Japan’s Select Sale of Yearlings in July.

Prices for quality yearlings at the sales have been strong in recent times, higher than the prices the clubs would have paid to Northern Farm. But the payback is that the horses that go to the clubs remain within Northern or Shadai’s sphere and, if good enough, return to the farms as stallions or broodmares.

A champion like Almond Eye, if sold at the yearling sale, could have been lost to a private owner. But by going into the racing club programme with Silk Racing, when she retired she returned to Northern Farm.

Ownership, viewed in traditional terms, is perhaps an illusion for the club members: while a lottery is held to see which few dozen out of a few hundred ‘owners’ might appear on the track with the horse after a win in Japan, it is a senior club representative who picks up the trophy at the post-race presentation.

But to get hung up on that is to miss the point a little. Investing in a Japanese racing club is something akin to supporting a sports team, it is an individual’s investment in their fandom and there is often a loyalty element involved.

“I’ve met plenty of people over a drink who have a share in two or three horses but they will tend to stay with the same organisation,” noted Johnson. “The joy of the ownership is basically saying I own a horse that’s successful, and that’s from the wealthy people in the syndicate to the salary man as well, they could all be in the same horse.”

While ownership in a club horse will likely end when a racing career ends, some clubs offer incentives that carry on connections beyond retirement. Carrot Farm club – peculiar among the Northern Farm affiliates – gives its investors an opportunity to continue associations through its mares. For example, when the American Oaks heroine Cesario retired, those who had invested in her racing career were offered first call on buying shares in her offspring, which include the Group 1 winners Epiphaneia, Saturnalia and Leontes, no less.

Whether or not the Japanese racing club model could work outside of Japan is open to debate and revolves, perhaps, around cultural differences and varying expectations from place to place. When all is said and done, the racing clubs are in a sense just beefed up fan clubs, on the one hand, and, on the other, business ventures of the entities that own them.

But, either way, the success of the most prominent clubs in Japan is testament to both the sharp sense of the Yoshida family’s foray into the sphere, and to the appetite among the sport’s Japanese fans to be connected more deeply with the JRA’s star horses.

The investment goes way beyond the success or failure of their weekend bets; the racing clubs are successfully connecting thousands of Japanese fans with some of the biggest stars in world racing, whether they really ‘own’ them or not.

Yahagi has substance to match his style